Sexual Harassment in The Workplace Legalities – Then and Now

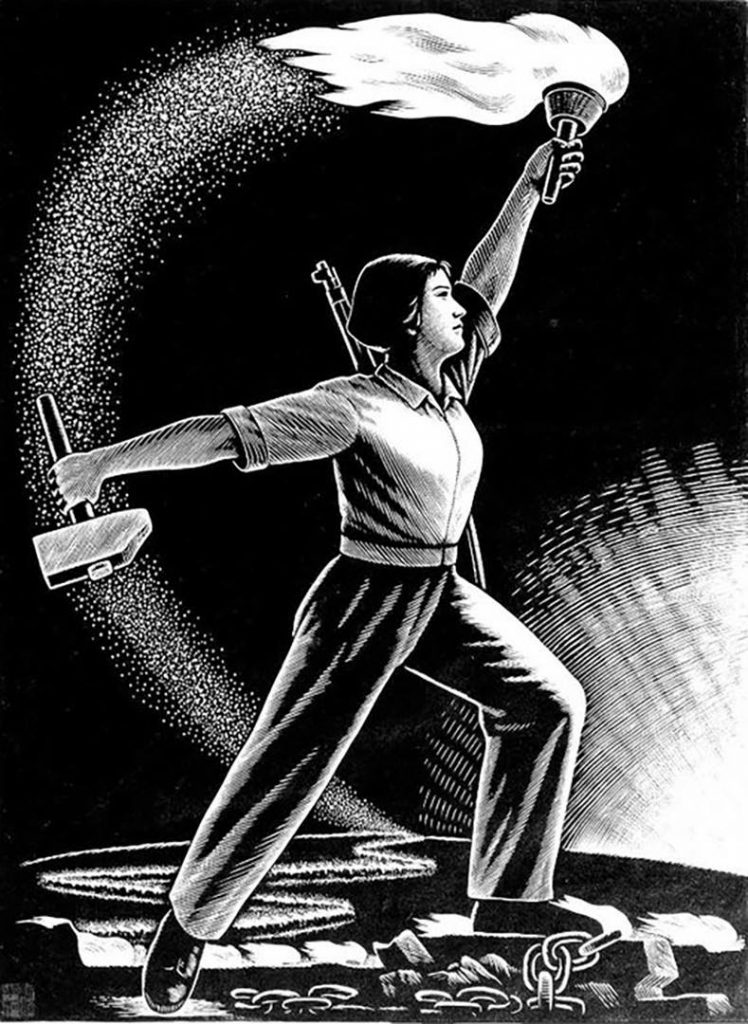

“A single spark can set the prairie alight,” print by Huang Xinbo, People’s Republic of China, 1972.

Brief History

Rajasthan currently has the highest occurrence of child marriages despite it being illegal and it was no different in the early 1990s. Bhanwari Devi was a Rajasthani government worker who was passionate about women’s rights. While she was involved with local women’s rights groups, campaigning against child marriages was especially important to her since she was a former child bride and speaking against it was frowned upon.

The gov of Rajasthan had launched a campaign against child marriage in the same vein, around the auspicious festival of Akshaya Trithi, where many marriages took place. She heard rumours of a family trying to marry off their barely 1 year old daughter in the town of Bhateri. While trying to reason with them, as a part of her job, the patriarchs of the family were enraged that a woman had authority over the ongoings of their family. Men from that family, ever so entitled to women’s bodies, married their one year old daughter off anyway. A few months later, they assaulted and raped Bhanwari Devi for having the audacity of being a woman, that too from a oppressed caste, for being in a position of power.

Bhanwari Devi followed due process and brought this case to the Rajasthani High Court, which threw it out claiming that a man could not possibly have participated in a gang rape in the presence of his nephew, and that no husband would idly watch his wife being gangraped.

Outraged by this, the case was then taken up by Vishaka and other women’s voluntary groups (now called NGOs) to the Supreme Court. In 1997, the SC laid down what is now called Vishakha Guidelines. Read more about Bhanwari Devi’s life here and here.

Vishakha Guidelines

Vishaka & others v. State of Rajasthan was a landmark case for working women’s rights in India, which until 1997 had no such domestic law protecting women in the workplace from harassment. The guidelines defined sexual harassment in the workplace as:

| * Unwelcome sexually determined behaviour (whether directly or by implication) as:Physical contact and advances. * A demand or request for sexual favours. * Sexually coloured remarks. * Showing pornography. * Any other unwelcome physical, verbal or non-verbal conduct of sexual nature. |

If a lawsuit was to be filed, it would have gone under Article 14, 15 and 21 of the Constitution under “right to life and personal liberty”. In the private sector, this could only be enforced with people defined as “employees” or “workers” under Industrial Employment Act of 1946, which left out millions of women engaged in unorganised, informal labour. The guidelines were upheld till a formal legislation was introduced 16 years later to enforce this legally.

Legislating Workplace Sexual Harassment – POSH Rules

The bill was introduced in 2007, and proposed in Lok Sabha in 2010. Dubbed POSH Rules, Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013 was legislated and it came into force in late 2013.

This was meant to extend the Vishakha Guidelines and provide a recourse for “aggrieved women” and “employees”, instead of “workmen” as defined in Industrial Disputes Act 1947. This is applicable to all government, public and private organisations to prevent and handle a hostile workplace. Any salaried, honorary or voluntary worker could appeal to an Internal Complaints Committee. The SC mandated every organisation of at least 10 employees to set up an Internal Complaints Committee (or ICC), and every organisation below that to set up an Local Complaints Committee (or LCC), to handle and redress such complaints. The ICC was to be led by female employees, with the committee being at least 50% women.

A handbook was published by the Ministry for Women and Child Development broadly categorises sexual harassment as the following:

| Quid Pro Quo ( ‘this for that’)Implied or explicit promise of preferential/detrimental treatment in employmentImplied or express threat about her present or future employment statusHostile Work EnvironmentCreating a hostile, intimidating or an offensive work environmentHumiliating treatment likely to affect her health or safety |

The Handbook details some examples of sexual harassment and expands on some underlying behaviours that would require further probing.

Criticisms of SHA (2013) – Failure of Enforcement

The Act, after much furor, finally included domestic as a part of “aggrieved women”, but excludes women working in agricultural sector and defense. The initial hesitation on the lack of enforceability would have been a cop out considering most companies still do not have an ICC in place, nor do they conduct sexual harassment seminars, despite penalties being placed upon them for non compliance (INR 5,000 – 25lakhs and upto 3 years of prison time).

Many have criticised the Act for the existence of a statute of limitations (3 months from the date of last harassment incident). The employer too has a deadline placed upon them to collect necessary evidence and take action within 3 months. The Act focuses more on conciliation, penalisation of false complaints (which is statistically low) and the absence of liability for the employer. It is too dependent on the existence of an Internal Complaints Committee which can exist only at the behest of the employer, further tipping the scales in their favour. It also requires a neutral third party from an NGO to participate in the Committee, making this logistically difficult. In mid 2018, to ensure compliance, the Ministry of Corporate Affairs amended the Companies (Accounts) Rules 2014 mandating that directors’ annual report show the company’s compliance with the Act.

Under this Act, there is currently no way to redress workplace sexual harassment in the era preceeding 1997, which still means Bhanwari Devi might still not see the justice she’s owed. Companies might choose to take up cases retrospectively, once again at their own mandate. There is an ongoing proposal to waive this statute of limitation and to instead have it as a “limitless time period”. Further explanation and analysis of this statute can be found here, here and here.

Failure of Enforcement – Abuse of Power by the ICC

Furthermore, the existence of the ICC does not guarantee justice either; the ongoing sexual harassment case against Tata Consultancy Services (TCS) by an infotech employee against her manager posits this. In an interview with Newsclick.in, she claims that the ICC treated her with prejudice and denied her lawfully owed services by asserting that she was “damaging the image of TCS”. She says that a member from the committee “managed to influence the external committee member and tried to threaten her of consequences for damaging the image of TCS”. The ICC also breached confidentiality which is required by the Act by releasing her identity and details of the harassment incident. She was repeatedly not allowed to resign, TCS transferred her within her company, which she says caused her further stress.

The complainant began the process of litigation making it the first sexual harassment case to reach the court from the IT industry in India. Her representatives, NDLF, FITE and UNITE labour unions were present in the court. A UNITE spokesperson demanded that the current ICC be dismantled and replaced by a group as dictated in the Vishakha Guidelines.

Empowerment of Working Women – Role of Unions

The repeated neglect of harassment survivors shows the clear abuse of power that big companies like TCS have displayed, necessitating a united struggle against sexual harassment in the workplace. As a collective, women have better access to legal representatives and other resources during cases of harassment, contract based work, salary negotiations, and other protections that would not be easier to find otherwise. Women do not have to suffer through unfavourable conditions alone, but together we gain equal footing to those who employ us and we are truly empowered in our fight for better working conditions and fair wages.

— Divya S, Member, UNITE